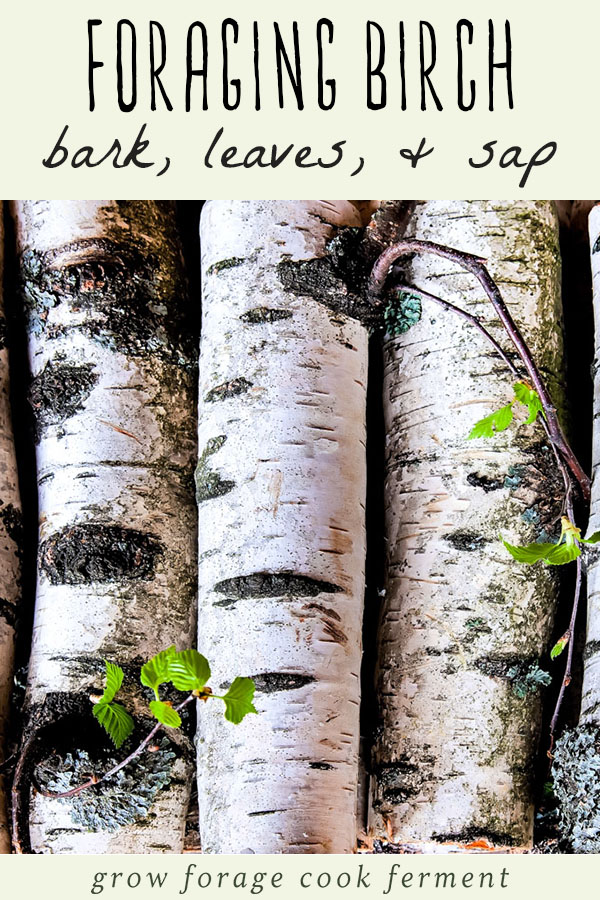

Birch trees are one of my fall and winter foraging favorites, and they have many edible and medicinal parts! In this post I’ll focus on the different parts of the birch tree you can forage, as well as how to be mindful of the tree’s health and longevity. Read on to learn more about foraging birch trees including birch bark, leaves, and sap!

Wildcrafting Weeds

If you want to learn more about the edible and medicinal weeds that surround us and how to use them, check out my eBook: Wildcrafting Weeds: 20 Easy to Forage Edible and Medicinal Plants (that might be growing in your backyard)!

Gather & Root Online Foraging Course

My online foraging course is a great way to learn about wild edible and medicinal plants! Sign up to learn more about the gather + root online foraging course here.

Foraging for Birch

As the weather cools, you may find yourself wandering through a forest or park in search of some classic fall scenery. Often this means coming across deciduous trees, their leaves flashing gold and crimson.

While these leafy trees make for glorious autumn vistas, some of them also offer an additional way to immerse yourself in the new season: you can eat them!

The birch tree is one tasty example, and there are many flavorful and healthy ways to make use of birch this fall.

Related: What to Forage in Fall: 30+ Edible and Medicinal Plants and Mushrooms

How to Identify Birch Trees (Betula spp.)

There are more than fifty species of birch trees in the world, and nineteen of those are native to the United States.

This means different birch species vary in terms of bark color, leaf size, and habitat, so you may want to consult a local tree guide to know what to look for in your area (here are a couple of good ones for western and eastern states).

One characteristic that is often helpful in identifying many members of the Betula genus is the horizontal markings, called lenticels, on their bark. These can be thin, like lines partway around the tree, or thick and rough, almost like healed-over gashes.

In most species, the bark is thin and papery, though it can vary in color from bright white (such as the paper birch), to a coppery red (such as the red birch).

Birch leaves are simple with serrated margins, and the trees are monoecious. This means they bear both male and female reproductive material on a single tree.

For birches, these reproductive parts are called catkins (to picture them, think of caterpillars dangling from twigs). Female catkins are clusters of seeds, while male catkins are clusters of pollen.

Birch Tree Foraging Tips

There is also so much variation in how to use birch, because most parts of the tree are edible and medicinal.

Foraging birch can range from minimally impactful (such as taking twigs and leaves), to potentially life-threatening to the tree (such as stripping it of its bark).

However, it is possible to forage all edible and medicinal parts of the birch tree in a way that allows the tree to continue growing healthily, as long as you are mindful of how much of the tree you are taking and when.

Here are some tips for foraging birch. I’ll start with the least invasive parts to forage and then describe the elements of the tree you have to approach with extra care.

Birch twigs, leaves, and catkins

Live twigs, fresh leaves, and even pollen catkins can be foraged from birches to make a peppery, minty tea rich in vitamin C.

Your best bet for birch tea during the colder months is to forage twigs. Look for young twigs that are still attached to the tree or have very recently fallen, perhaps on a live branch that broke off in a wind storm.

Twigs should be flexible under pressure, so they shouldn’t snap easily when bent. If they are brittle, they’re probably dead and not useful for tea.

When they’re fresh and alive, the twigs should also emit a smell, similar to wintergreen gum, when broken and scratched.

If the twigs have leaf buds, just remember that every bud you take could have been new leaves for the tree, so try not to take too many from one tree.

In the springtime, look for leaves and catkins to liven up your birch tea! When collecting leaves for tea, you don’t need many for a nice, steaming cup.

Depending on your preference, you only need about three young leaves for a single serving. If the tree is producing pollen catkins, grab some of those as well, because you can add them to your tea.

Of course, if you have a birch pollen allergy be cautious about handling birch pollen.

Because birch trees contain a compound similar to aspirin, they are also sometimes used for topical pain treatment.

If you plan make a medicinal infused oil (see more on that below), you’ll need to collect at least a jar’s worth of birch pieces, such as leaves and twigs.

Medicinal fungi growing on birch trees

If you’re foraging from a birch tree and notice fungus growing out of its bark, it could be one of several beneficial fungi that thrive on birch trees.

Birch polypore (Fomitopsis betulina), which looks like a fluffy pancake protruding from tree bark, has proven in studies to have antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory properties. Be sure to learn more about identifying this fungus before you take any home.

If you encounter a hardened, burnt-looking fungus on a birch tree, it could be the medicinal and highly sought-after chaga mushroom!

If you’re interested in exploring the medicinal properties of chaga and learning how to sustainably harvest a portion of the mushroom, read more about identifying and harvesting chaga, as well as how to process it.

Tapping birch trees for syrup

Collecting birch sap is a more time-intensive way to enjoy the refreshing flavor of birch, and it can also be hard on the tree.

Not only does collecting sap require making an incision in the tree deep enough to reach sap flow in the xylem, it also takes nutrients and water that the tree would otherwise use to sustain itself and support new growth.

However, this doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t ever forage birch syrup. You can minimize damage to the tree by choosing a healthy birch that appears to have good access to resources such as water, sun, and rich soil.

You can also elect for a tapping method that is less invasive than drilling, such as using a knife and a spile to make a small incision in the tree and catch the sap as it drips out.

Sap tends to start flowing in early spring. Read up on birch tapping basics now so that you’re ready to catch that small window of time when it arrives with the thaw!

Ethical Foraging for Birch Bark

Potentially the most invasive way to forage birch is to use its bark, which can be processed into a tasty, non-rising birch bark flour or made into a medicinal birch bark tea.

While Indigenous People and others who’ve historically relied on birch as part of their survival developed ways of removing strips of bark without killing the tree, this is still risky and can’t be justified by those of us who aren’t foraging birch to survive.

For this reason, focus on foraging birch bark only from trees that have very recently fallen or from trees that are about to be cut anyway.

In order to understand why taking bark from a tree can greatly harm or even kill the tree, I highly suggest brushing up on the basic parts of a tree trunk.

Essentially, it is important to realize that trees rely on vertical transport methods to move essential water and nutrients from their roots and leaves to the rest of the tree.

If these vertical pathways are severed or too greatly diminished, the tree can suffer and even die. Even if you managed to only take the outer bark, this still weakens the tree’s defenses against external forces.

When people do harvest bark from standing trees for survival or because they grew the tree for that purpose, they remove vertical strips from the tree.

This is because taking bark in circular strips from around the trunk risks girdling the tree.

This method starves the tree to death and is sometimes used in forestry practices to create dead standing trees (snags) for wildlife habitat, but you definitely wouldn’t want to do it to a tree on accident!

Related: What to Forage in Winter: 30+ Edible and Medicinal Plants and Fungi

Processing and Using Birch

There are various techniques for foraging and processing different parts of the birch tree, and you’ll discover your own preferences through experimentation.

It might help to start out with a recipe in mind, so here I’ll describe some of the basic ways birch is processed into tea, infused oil, and flour.

How to Make Birch Tea

The inner bark, twigs, and leaves of birch trees have powerful analgesic painkiller properties. They are also anti-inflammatory, astringent, aromatic, and assist the body in reducing fever. The easiest way gain all of the benefits of birch is to make a tea.

To make birch tea from twigs, choose the freshest tips (a few inches) of the twigs you foraged and snap those into a glass jar or cooking pot.

You can either heat the water (not quite boiling) and pour it over the twigs, covering and letting steep as desired and strain, or you can heat the twigs in a pot, strain, and enjoy.

The pot-heated method would be particularly satisfying around a campfire!

Birch tea can be made from birch bark, paying special attention to the ethical foraging concerns listed above.

You can also purchase sustainably harvested birch bark from Mountain Rose Herbs, my favorite place for organic dried herbs.

Make tea from birch leaves by selecting about three leaves per cup of water and steeping them in freshly boiled water until the tea is as strong as you’d like.

Some people claim boiling causes the beneficial birch compounds and aromas to quickly evaporate, so experiment with temperature until you’re satisfied.

You can combine leaves, twigs, and even catkins into one tea brew if you wish. For a more involved birch tea process, roast the twigs, grind, and steep them.

Birch Infused Oil

Birch bark and leaves have anti-inflammatory properties so they make an effective infused oil for topical pain relief. The birch infused oil could also be used to make an herbal salve.

To make an infused oil for sore muscles, collect birch bark, leaves, or both, and submerge them in a carrier oil, such as olive oil, for at least a few weeks.

You can learn more about using birch for topical healing in this video or see this recipe for birch leaf infused oil.

Birch Bark Flour

Birch bark flour is made from the tree’s inner bark. This requires that you strip the inner bark, dry it, and grind it up into a powder.

In combination with another flour, you can use birch flour in breads and cookies for a nutritious change of pace!

Whether you’d like to make a warming tea or tap into the xylem for some refreshing sap, I hope this post has piqued your curiosity about birch trees and inspired you to appreciate them for their edible properties, as well as their stunning fall foliage!

Lucia Hadella is an environmental writer from Talent, Oregon. Her interests include human-environment interactions, climate change, and resilient futures. Lucia recently graduated from Oregon State University with a B.S. in Natural Resources and an M.A. in Environmental Arts & Humanities and moved to Columbus, OH this winter to begin her urban nature adventure! Find her on Instagram @true_nature_filter.

Can you make a tincture with the inner birch bark?

Yes, you can.

Great page thanks! How to treat Birch if you like to preserve it….. take parts of it inside your home as a decoration and keep the bark on and make it look like it does out in nature for many years?

I see a lot of fallen, dead birch wood when I go camping. Can you also collect and use inner wood from dead trees to avoid harming the living ones? (Provided the wood that I find is in good condition)

Hi, Emily! Yes, you can definitely do that.

I find willow bracket fungus growing on white and yellow birch. It resembles chaga except the bottom suede leather surface that produces spores.

Do these tips apply to river birch in the Southern United States?

When collecting and using for oil and or tea, can you dry the bark and leaves and use later? I was told that using dried ingredients are better for infusing oils? Thanks.